The Hunger Games.

For those of you unfamiliar with author Suzanne Collins’ widely popular fictional trilogy, they tell a story of a post-apocalyptic North America. In short, an oppressive government forces teenagers to battle one another to the death in a nationally broadcast ritual known as the Hunger Games (now a film playing at your local theatre). Katniss Everdeen, the protagonist and narrator, describes the arena (battlefield) environment for the Hunger Games as primarily scrub terrain, laden with boulders, scruffy bushes and hidden caves. She mentions that most tributes died from bites from venomous snakes, eating poisonous plants/berries or going insane from thirst.

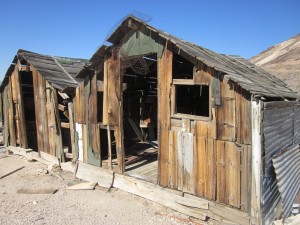

This past week-end I visited an area that could have been the film’s movie set. Desolate territory. Yes, rhyolite is a mineral. Rhyolite is also a ghost haunt hidden in Nevada’s Amargosa Desert. Having just finished reading these books, visiting Rhyolite was a snapshot into North America gone awry. An eerie Dora-the-Explorer Moment, perhaps, but one worth taking.

I’d been in Bishop, California, observing a young lady’s ninth birthday as well as Mother’s Day. The lack of spring snow cover combined with sunny temps permitted celebratory hikes and picnics in the Sierra Nevada Mountains with the ever present family festivities and gifts. Driving home on Sunday, having wound my way through Death Valley, I decided to detour to Rhyolite. Although I was aware of this little-known community, Rhyolite’s Goldwell Open Air Museum has just been selected as a Nevada “Natural Treasure.” Say, what???

Rhyolite is located about 120 miles northwest of Las Vegas near the eastern edge of Death Valley. The town sprang to life in early 1905 as one of several mining camps hobbled together after precious ore was discovered in the region. According to government statistics, by 1907 the camp had “electric lights, water mains, telephones, newspapers, a hospital, a school, an opera house, and a stock exchange.” Add to that,“fifty saloons, thirty-five gambling tables, cribs for prostitution, nineteen lodging houses, sixteen restaurants, six barber shops, a public bath, weekly newspaper and stage coach transportation.” At its peak the town’s population varied between 3,500 and 5,000.

Easy come. Easy go. The Montgomery Shoshone Mine, the region’s largest producer, closed in 1911. The population took a nosedive, falling below 1,000. By 1920, almost zero. That’s when the town turned into a genuine ghost town, little noticed tourist attraction, and occasional motion picture set. It was a group of well-respected Belgian artists led by Albert Szukaslski who invigorated this beleaguered area. In 1984, the artists began creating large scale, on-site sculptures which still exist today. That the “on-site” was the Mojave desert, making that vast and challenging wasteland integral to their work, is what makes this outdoor museum both spectacular and profound.

Saloon Owner Tom Kelly’s Bottle House, made of beer and liquor bottles he collected from local saloons

Rhyolite may not be a destination of choice for the American tourist but artists from all over the world know of and visit this place. The Red Barn Art Center, located nearby, offers artist residency and workspace programs.

Ghost town. Open air sculpture museum. Artist colony.

Worth a Visit.

What a terrific add-on to your road trip! Very interesting…

totally had to know what people used rhyolite for and aside from jewelry and landscape or knicknacks you could consider building a house with it.

http://www.rhyolitesite.com/bottle1.htm

see you on Thursday in Basalt. 6PM….we will have some of the usual suspects in attendance.

Yes. Now that I’m going to be there more, and, this is the beginning of that, it’s going to be fun and challenging to find my way and find my fit. All packed and ready to roll early tomorrow morning.

Wow! I would never have known about Rhyolite. What strange and eerie scenes, and interesting history. Thanks for sharing!

COOL! We’ll have to check that out the next time we visit Death Valley.

Mary, I enjoyed your post so much that I did a bit of “homework” and researched the internet for more information about the ghost town Rhyolite, the Rhyolite Preservation Society and the Belgian artist who created the acrylic statutes. Very interesting! I must admit that I had never heard of this interesting place before – thanks for writing a post about it! I am afraid I will probably never get to visit Rhyolite in person though.

Changing the subject “a bit” here: I do love Thomas Keller, his “Ad Hoc at Home” cookbook is wonderful and yes, I agree, his recipes are oftentimes sooooo complex, that I need some serious planning to get through them, they certainly are worth it though. Any one particular recipe that is a ” must try”?

Thanks again for your interesting post! It is always great to learn about places that I had never heard of before.

Really interesting post Mary! I loved it! I would have never known about this place otherwise.

What an interesting post. I would love to visit there someday!